Who is responsible if you hit a cow or horse on the road?

That answer depends on where the crash happened, what the animal’s owner did (or failed to do), and what the law says about livestock on the road. In California, liability in these situations typically falls on the owner. But that’s not the case in every state. In certain states, liability laws limit your ability to hold anyone accountable, even after a serious crash involving a cow or horse.

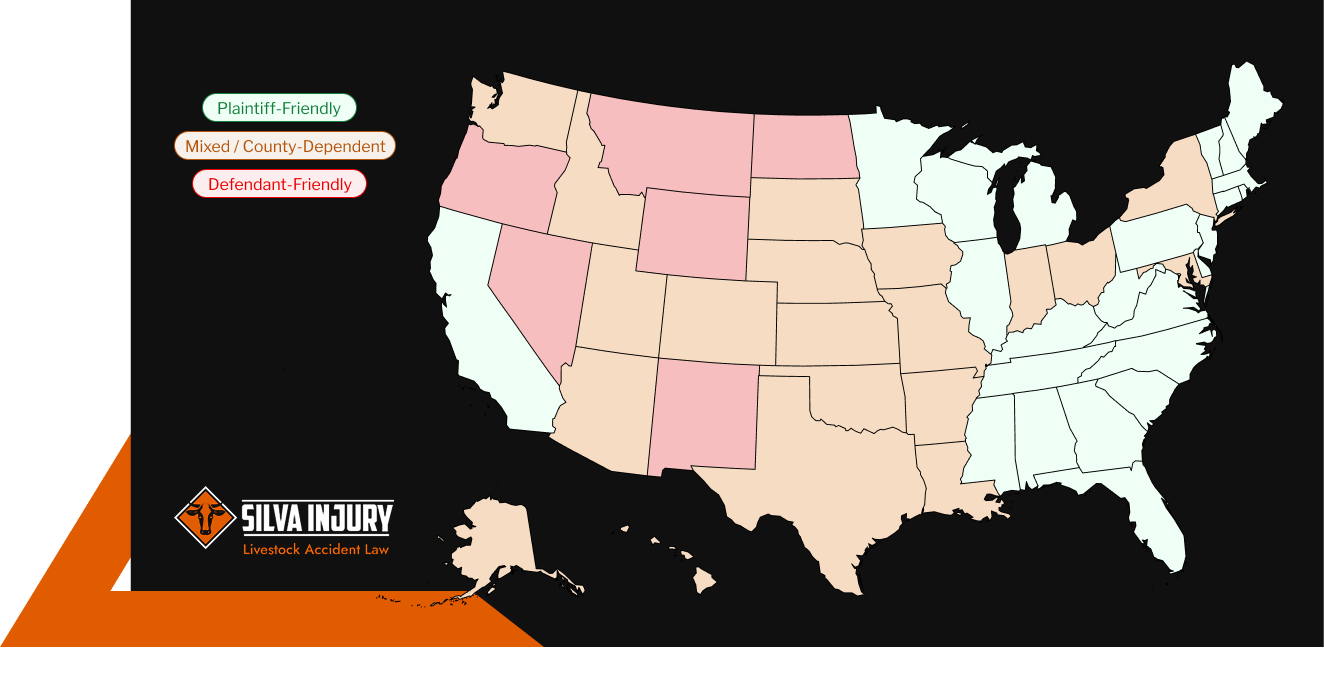

Below you’ll find a state-by-state breakdown of livestock laws to help you understand the basics of accident liability in your state. You’ll also find answers to your most pressing questions after experiencing a collision with a cow, horse, or other type of livestock.

Important Disclaimer: Livestock accident laws vary widely by state and sometimes by county. This guide gives a claimant-focused overview. It is not legal advice. For case-specific guidance, contact our law firm for a free, no-obligation consultation.

Livestock Accident Liability – A 50-State Overview

| State | Overview | Doctrine | Key Liability Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners liable when livestock are allowed to run at large and cause a crash. |

| Alaska | Mixed / County-Dependent | Hybrid | Local rules vary; negligence required outside clearly restricted areas. |

| Arizona | Mixed / County-Dependent | Open Range / No-Fence Districts | Open range limits claims; in no-fence districts, owners must confine and may be liable. |

| Arkansas | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In (local stock-laws) | Most areas require restraint; proof can hinge on county history and notice. |

| California | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In / Limited Open Range | Owners liable on fenced/bounded highways; check for rare open-range pockets. |

| Colorado | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fence-Out default / local fence-in | Rural fence-out; municipalities often fence-in with owner liability. |

| Connecticut | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Duty to restrain; negligence if animals roam onto public ways. |

| Delaware | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners responsible for preventing at-large livestock; liable for roadway crashes. |

| Florida | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In (closed range) | Statewide ban on livestock at large; owner negligence supports liability. |

| Georgia | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Statutes bar animals from running at large; violations bolster negligence. |

| Hawaii | Mixed / County-Dependent | Hybrid | County rules vary; negligence standard common in populated areas. |

| Idaho | Mixed / County-Dependent | Open Range / Herd Districts | Open range limits claims; herd districts require fencing and impose liability. |

| Illinois | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Running at large prohibited; negligent restraint creates liability. |

| Indiana | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In (negligence) | Negligence with proof of notice/foreseeability and poor restraint. |

| Iowa | Mixed / County-Dependent | Negligence | Ordinary negligence governs; show inadequate restraint or supervision. |

| Kansas | Mixed / County-Dependent | Mostly Fenced-In / some open-range | County status controls; fence-in counties favor claimants. |

| Kentucky | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Statutory duty to restrain; owners liable for animals running at large. |

| Louisiana | Mixed / County-Dependent | Highway bans + local stock-laws | Stronger liability on covered highways/stock-law areas; fact-specific elsewhere. |

| Maine | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Duty to confine; liability if animals at large cause harm. |

| Maryland | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In / Negligence | Reasonable care required to keep livestock off highways. |

| Massachusetts | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners liable for injuries/damage from animals at large. |

| Michigan | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | At-large livestock prohibited; negligent escapes create liability. |

| Minnesota | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Negligent containment leads to owner liability. |

| Mississippi | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners must restrain livestock; liability for animals on highways. |

| Missouri | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In (few open-range) | Most counties fence-in; confirm local status and notice. |

| Montana | Defendant-Friendly | Open Range (exceptions) | Open range protects owners; fenced/municipal areas impose duties. |

| Nebraska | Mixed / County-Dependent | Hybrid | Municipal bans common; rural cases hinge on negligence and locale. |

| Nevada | Defendant-Friendly | Open Range (+ fenced-highway carveouts) | Drivers assume risk in open range; liability on fenced/closed highways. |

| New Hampshire | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Duty to restrain; liability for animals at large. |

| New Jersey | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners liable for roaming livestock causing damage. |

| New Mexico | Defendant-Friendly | Open Range (municipal/highway carveouts) | Open range limits liability; closed areas impose duties. |

| New York | Mixed / County-Dependent | Negligence (Hastings) | Ordinary negligence applies to roadway livestock cases. |

| North Carolina | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Statewide fence-in; owners liable for animals on roadways. |

| North Dakota | Defendant-Friendly | Open / Closed range mix | County/district status controls; negligence in closed-range areas. |

| Ohio | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In | Liability when livestock are at large due to negligent restraint. |

| Oklahoma | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fenced-In (some open-range) | Varies by county; fence-in areas impose duty and liability. |

| Oregon | Defendant-Friendly | Open Range / Livestock Districts | Districts impose fence-in; open range limits duty. |

| Pennsylvania | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In / Negligence | Foreseeability + failure to confine supports liability. |

| Rhode Island | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Strict duty to fence; owners liable for animals at large. |

| South Carolina | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Open range abolished; owners must contain livestock. |

| South Dakota | Mixed / County-Dependent | Fence-Out default / closed-range districts | District status controls; liability stronger in closed-range zones. |

| Tennessee | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners liable for damages caused by animals at large. |

| Texas | Mixed / County-Dependent | Open Range default / stock laws | Closed-range on many highways and in stock-law counties; verify locale. |

| Utah | Mixed / County-Dependent | Open Range / local restrictions | Open range in rural areas; restrictions and highways impose duties. |

| Vermont | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners responsible for keeping livestock enclosed; liability for escapes. |

| Virginia | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In (some fence-out) | Most counties fence-in; confirm locality; negligence creates liability. |

| Washington | Mixed / County-Dependent | Mostly Fenced-In / some open range | Stock-restricted areas favor claimants; open range limits duty. |

| West Virginia | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Duty to restrain; owners liable for animals at large. |

| Wisconsin | Plaintiff-Friendly | Fenced-In | Owners may be liable for damages caused by livestock at large. |

| Wyoming | Defendant-Friendly | Open Range (fenced-highway liability) | Owners liable for livestock on fenced public highways; limited elsewhere. |

| District of Columbia | Plaintiff-Friendly | Urban animal-control | At-large animals prohibited; negligence for failure to restrain. |

Plaintiff-Friendly States – Livestock Accident Liability

Alabama Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (Statewide)

Owner Liability: Owners are strictly prohibited from negligently or willfully allowing livestock to run at large on highways; strict liability applies for crop or property damage, though vehicle collision liability requires proof the owner knowingly placed the animal.

Plain-Language Summary: Alabama requires livestock owners to contain animals everywhere—there are no open-range areas. However, while property damage is strictly actionable, a collision claim requires proving the owner intentionally or negligently let the animal onto the road.

Context & Details: Alabama’s statutes (e.g., § 3-5-2) make it a misdemeanor for livestock to be at large, anywhere in the state, establishing a strong legal foundation for liability. Still, for vehicle repairs or injury claims, courts often require evidence the owner “knowingly or willfully” put the animal on the road (e.g., prior reports of escape). Effective claimant tools include trooper or highway patrol logs, neighbor testimony on prior escapes, and photos of the damaged barrier. Defensive strategies rely on showing escape was sudden, weather-driven, or due to vandalism, but absent proof, these are weak.

Sources: Ala. Code § 3-5-2 · Ala. Code § 3-5-4

California Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Mixed (Fenced-In on Most Highways; Isolated Open-Range Pockets)

Owner Liability: On fenced highways and enclosed roads, negligence gives rise to liability; open-range areas are rare—claimants must verify location to hold owners accountable.

Plain-Language Summary: Most California roads are fenced or restricted, making owner liability more likely when livestock escape. But rare open-range zones mean you must confirm the road’s status.

Context & Details: Generally, California’s fencing laws require livestock confinement (Food & Ag Code § 16902), with liability for negligence resulting from poor maintenance. Some remote, rural counties still have open-range areas, shifting risk to motorists. Evidence of broken fencing, repair neglect, or prior incidents can build strong claim cases in fenced-in zones.

Sources: Cal. Food & Agric. Code § 16902

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in California?

Connecticut Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (Statewide)

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock from entering public roads; negligence (poor fencing or supervision) supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Connecticut requires livestock containment everywhere—if animals escape and cause a crash, evidence of poor fencing or oversight often proves the owner’s fault.

Context & Details: Connecticut’s laws impose a clear duty to keep livestock off public ways. Courts analyze whether fencing met reasonable standards, whether gates were secured, and if repairs were timely. Owners sometimes argue unavoidable weather damage, but successful claims often hinge on demonstrating repeated escape events or dismissed maintenance needs, using official reports and photos.

Sources: Conn. Gen. Stat. (Chap. 435 excerpt)

Delaware Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (Statewide)

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from straying; simple negligence can create liability for damages.

Plain-Language Summary: Delaware law holds owners responsible when livestock damage roads or crossways due to poor containment.

Context & Details: Delaware applies a fenced-in rule statewide. Proving negligence often involves showing lost livestock from neglected fences or gates, and prior complaints. Given the state’s small size, law enforcement documentation and neighbor statements are particularly valuable for showing patterns of neglect.

Sources: 3 Del. C. ch. 77 Stray Livestock · 3 Del. C. § 7706

District of Columbia Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from roaming; negligence or failure to act supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: D.C. follows a fenced-in approach, requiring livestock to be securely contained. Owners are generally responsible when animals stray due to poor maintenance or lack of supervision.

Context & Details:

In the District of Columbia, ordinances require livestock owners to prevent animals from running at large, particularly in areas near public roads or residential property. Claims are strongest when evidence shows the owner failed to maintain proper fencing, ignored prior escapes, or violated local animal control laws. Common evidence includes animal control records, neighbor complaints, or photographic proof of damaged enclosures. While an owner might argue that a third party caused the escape, these defenses require convincing proof. Because D.C. is heavily urbanized, even a single instance of livestock at large can result in swift enforcement and bolster a plaintiff’s case.

Sources: D.C. Code § 8-1808

Florida Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (Statewide Closed Range)

Owner Liability: Owners are liable if livestock are found on roads due to negligence—Florida has no open-range exceptions.

Plain-Language Summary: Florida banned open-range across the board. Livestock collisions usually result in liability if the owner failed to contain the animal.

Context & Details: Florida statutes clearly prohibit livestock roaming public roads without containment. Cases typically hinge on evidence of broken fences, open gates, or prior escapes. Courts rarely accept weather damage defenses without proof of timely repairs. Police and FHP records documenting repeated issues can be winning evidence.

Sources: Ch. 588 Fla. Stat. (Livestock at Large) · § 588.15 Fla. Stat.

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Florida?

Georgia Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (Statewide, but some rural areas informally less enforced)

Owner Liability: Owners must not permit livestock to roam; negligence supports liability, though enforcement in remote areas may be inconsistent.

Plain-Language Summary: Georgia law bars livestock from running loose, and most counties enforce fencing requirements—especially where neighbors or law agencies are involved.

Context & Details: Georgia imposes a statewide responsibility on owners to prevent livestock at large, with negligence sufficient for civil claims. In rural areas, enforcement can lag, but documented history of escapes or fencing flaws strengthens a case. Owners often claim trespass or sudden damage; claimants should rapidly gather evidence and prior reports.

Sources: O.C.G.A. § 4-3-3 · O.C.G.A. § 4-3-12

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Georgia?

Illinois Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock; negligence or statutory violations can lead to liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Illinois law favors plaintiffs by requiring livestock containment and allowing recovery when owners fail to meet that duty.

Context & Details:

Illinois statutes make it unlawful for livestock to run at large, and owners are liable for damages caused by escaped animals if negligence is involved. Courts consider whether the owner used “ordinary care” in maintaining barriers, securing gates, and monitoring enclosures. Evidence such as police accident reports, prior county citations, or photos showing deteriorated fencing can strengthen a case. Defenses typically focus on unforeseeable third-party interference, but these are less persuasive without proof. The fenced-in doctrine makes Illinois generally favorable to claimants.

Sources: 510 ILCS 55/ – Domestic Animals Running at Large

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Illinois?

Kentucky Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must keep livestock contained; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Kentucky’s livestock laws require reasonable efforts to prevent escapes, with courts often favoring claimants when barriers are inadequate.

Context & Details:

Kentucky statutes prohibit livestock from running at large, and owners are liable if their negligence leads to damages. Courts assess whether fencing was suitable for the type of livestock and terrain, as well as the owner’s diligence in inspection and repair. Frequent issues include decayed wooden fencing in rural areas and gates left unsecured. Claimants strengthen their case by gathering visual evidence, neighbor statements, and records of prior incidents. Kentucky’s fenced-in doctrine generally makes it favorable for plaintiffs.

Sources: KRS 259.210

Maine Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock; negligence supports liability for damages caused by escapes.

Plain-Language Summary: Maine law favors claimants by placing the burden on owners to keep livestock off roadways and allowing recovery when they fail to do so.

Context & Details:

Maine’s statutes prohibit livestock from running at large, with owners facing liability when negligence is proven. Courts look at factors like the adequacy of fencing for Maine’s harsh winters, whether gates were secured, and the owner’s inspection frequency. Ice damage, snowdrifts, or fallen trees are common causes of fence breaches, but owners are still expected to act promptly. Claimants should gather photographs, weather reports, and any prior complaints to local officials.

Sources: 7 M.R.S. § 4011

Massachusetts Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock; negligence and statutory breaches can establish liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Massachusetts law strongly favors plaintiffs, requiring livestock containment and penalizing owners for negligence.

Context & Details:

Under Massachusetts law, livestock running at large creates a presumption of owner fault unless they can show due care. Courts weigh the adequacy of barriers, inspection frequency, and whether the owner responded to prior incidents. Common defenses involve claims of sudden, unforeseeable escapes, but these require credible proof. Gathering visual evidence and witness statements is key for claimants.

Sources: Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140, § 155

Michigan Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must not “permit” livestock to run at large; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Michigan law expects livestock to be contained, giving claimants a strong case when negligence is evident.

Context & Details:

Michigan prohibits livestock from running at large and holds owners accountable when animals escape due to poor maintenance or oversight. Claims are often supported by showing neglected fencing, faulty gates, or prior incidents of livestock on the road. Evidence from police reports, neighbor statements, or prior citations can strengthen the case. While owners can raise unforeseeable-escape defenses, a documented history of problems or visible disrepair in enclosures is usually persuasive for claimants.

Sources: MCL 433.11 et seq.

Minnesota Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Minnesota requires livestock containment and allows recovery when owners fail to maintain reasonable barriers.

Context & Details:

Minnesota law prohibits livestock from running at large and holds owners liable when negligence is shown. Courts consider whether the owner maintained adequate fencing for the type of livestock and local conditions, such as winter snow loads or spring flooding. Evidence like fence-condition photos, prior incident reports, and neighbor testimony is persuasive.

Sources: Minn. Stat. § 346.16

Mississippi Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Mixed (Fenced-In with Open Range Counties)

Owner Liability: Liability depends on county designation; fenced-in counties favor plaintiffs, while open range areas protect owners.

Plain-Language Summary: Mississippi’s livestock liability rules vary by county, making location the key factor in claim viability.

Context & Details:

In fenced-in counties, livestock owners must contain their animals and can be held liable for damages caused by escapes. In open range counties, owners have no general duty to prevent livestock from being on the road unless specific conduct (like intentional herding onto a roadway) is proven. Claimants must confirm the county’s designation and collect evidence such as local ordinances, prior complaints, and photos of the containment area.

Sources: Miss. Code § 69-13-111

New Hampshire Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must contain livestock; negligence or statutory violation can establish liability.

Plain-Language Summary: New Hampshire requires owners to keep livestock secured, and violations can create clear liability.

Context & Details:

While New Hampshire is less agricultural than many states on this list, the same fenced-in principle applies. Claims often arise from hobby farms or small-scale operations, where fencing may be improvised or outdated. Courts examine whether owners acted reasonably under the circumstances, and prior escape history weighs heavily in a plaintiff’s favor.

New Jersey Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: New Jersey enforces strict containment duties for livestock owners.

Context & Details:

Cases often center on the adequacy of enclosures, with attention to whether the owner knew of weaknesses or escape risks. In suburban or exurban areas where farmland borders public roads, the courts have little patience for owners who fail to inspect and maintain barriers.

Sources: N.J. Stat. § 4:20-16

North Carolina Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In (statewide; open range abolished)

Owner Liability: Owners must keep livestock contained; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: North Carolina requires livestock containment and generally favors plaintiffs where owners are careless.

Context & Details:

While some counties historically had open range traditions, the state has fully moved to a fenced-in requirement. Broken fencing, unsecured gates, or ignoring escape reports can all establish negligence. Plaintiffs often bolster cases with photos, repair invoices, or witness accounts of prior escapes.

Sources: N.C. Gen. Stat. § 68-16

Pennsylvania Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must contain livestock; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Pennsylvania requires livestock containment and has a long history of enforcing this duty.

Context & Details:

Courts weigh whether the owner acted reasonably to prevent escapes. Evidence of ignored warnings, poor maintenance, or repeated breaches often leads to findings of liability.

Sources:

3 P.S. § 584 (Certain animals not permitted to run at large) ·

States’ Fence Statutes: Pennsylvania (NALC)

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Pennsylvania?

Rhode Island Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Rhode Island applies a straightforward containment rule.

Context & Details:

Though agricultural operations are limited, cases still arise, particularly in rural or equestrian communities. Poor fencing or gate security is the most common basis for claims.

Sources: R.I. Gen. Laws § 4-14-1

South Carolina Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must keep livestock enclosed; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: South Carolina enforces strict containment obligations.

Context & Details:

The state moved away from open range decades ago. Courts emphasize whether owners had prior knowledge of escape risks and took reasonable corrective action.

Sources: S.C. Code § 47-7-110

Tennessee Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must keep livestock contained; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Tennessee enforces livestock containment and favors plaintiffs where owners are careless.

Context & Details:

Broken fencing, ignored warnings, and repeated escapes all weigh heavily toward liability. Plaintiffs often succeed by showing the owner had prior notice of the issue.

Sources: Tenn. Code § 44-8-401

Vermont Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must contain livestock; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Vermont applies a strict containment rule.

Context & Details:

Most disputes focus on fence maintenance and whether owners acted promptly after discovering breaches.

Sources: 20 V.S.A. § 3541

Virginia Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must keep livestock enclosed; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Virginia enforces containment duties with limited exceptions.

Context & Details:

Evidence of repeated escapes or ignored warnings can be decisive in establishing liability.

Sources: Va. Code § 55.1-2810

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Virginia?

West Virginia Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must contain livestock; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: West Virginia follows a containment rule.

Context & Details:

Claims often involve poor fence maintenance or repeated escape incidents.

Sources: W. Va. Code § 19-18-3

Wisconsin Plaintiff-Friendly

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Wisconsin requires containment and has clear statutory standards.

Context & Details:

Courts examine whether owners took reasonable precautions and responded promptly to known risks.

Sources: Wis. Stat. § 172.01

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Wisconsin?

Mixed / County-Dependent States – Livestock Accident Liability

Alaska Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range in Much of the State; Fence-In via Local Ordinance)

Owner Liability: Owners in “controlled livestock districts” must contain livestock and may face liability; in open-range, liability is limited absent statutory carveouts or gross negligence.

Plain-Language Summary: Some Alaskan boroughs require containment—but in most rural areas, animals may roam, and drivers bear more risk unless local rules provide otherwise.

Context & Details: Alaska law allows establishment of livestock districts via court order (see § 3-35-010), requiring owners to prevent animals from being at large. In regions without such districts, loose livestock on roadways may not lead to liability unless egregious negligence can be shown. For claimants, identifying the crash location’s jurisdiction is critical. Documentation of fencing condition, prior complaints, or resident testimony is key where local statutes apply—and nearly essential for success.

Sources: AK Stat. § 03.35.010 (Controlled Livestock Districts; animals at large) · AK Stat. § 03.35.050 (Impounding animals running at large)

Arizona Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range Default; Owners Responsible in “No-Fence” Areas)

Owner Liability: In open-range zones, drivers must exercise care; in officially defined no-fence districts, owners must restrain livestock and can be liable for negligence.

Plain-Language Summary: In many rural Arizona areas, drivers assume risk. But if the crash happened in a “no-fence” district, the owner is legally expected to confine livestock and can be held responsible for an escape.

Context & Details: Arizona law designates certain areas as no-fence districts (A.R.S. § 3-1427), where owners are required to contain livestock. Claimants must verify whether the crash site is in such a district—if so, focus on evidence like prior escapes or poor gate maintenance. In open-range zones, proving liability is tougher unless there’s clear misconduct or evidence the owner disregarded known risks. GIS maps and municipal records help pinpoint boundary status.

Sources: A.R.S. § 3-1427 (No-Fence Districts) · UA Extension: Open Range Law

Arkansas Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (County-Level Stock Laws Can Impose Fence-In Duties)

Owner Liability: In counties with stock law districts, owners must restrain livestock and may be liable for damages; in others, open-range principles may apply unless negligence is shown.

Plain-Language Summary: Arkansas allows counties to require livestock containment. Where such laws exist, owners can be held responsible for escapes—where they don’t, proving liability becomes harder.

Context & Details: Through petition and vote, counties may adopt stock laws (see § 14-387-205), creating areas where livestock cannot roam freely. In those zones, escape due to poor fence maintenance supports liability claims. Conversely, in non-stock districts, claimants must prove negligence. Important evidence includes fence photos, past escape history, and county voting records.

Sources: Ark. Code § 2-38-301

Colorado Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range Statewide; Local Municipalities Can Impose Containment Rules)

Owner Liability: In municipalities or closed-range districts, owners must contain livestock; outside those areas, open-range norms limit liability absent gross negligence.

Plain-Language Summary: Most of Colorado follows open-range rules, so owners aren’t automatically responsible. But in towns or districts with containment laws, they may face liability if animals escape.

Context & Details: Colorado maintains open-range standards by default, but local governments may adopt fence-in ordinances. Claimants have stronger cases in those zones by showing poor upkeep or escape history. On non-designated roads, claims need exceptional proof—such as willful animal release or flagrant neglect.

Sources: C.R.S. § 35-46-102

Hawaii Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners are expected to confine livestock; liability typically arises from negligence in containment.

Plain-Language Summary: Hawaii law treats escaped livestock on roads as a preventable hazard, making owners responsible when poor maintenance or oversight is to blame.

Context & Details:

Hawaii’s approach is essentially “fenced-in” — livestock must not be allowed to roam freely, and owners can be held liable for damages when containment failures occur. This often comes into play in rural or agricultural areas where roads pass close to grazing land. Courts look at whether fencing was adequate for local conditions, including salt-air corrosion near the coast or erosion in volcanic terrain. Claimants should document the state of barriers, prior incidents, and whether the owner ignored community or police warnings. Defenses that blame sudden storms or vandalism are possible but less effective without corroborating evidence.

Idaho Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Open Range with Local Exceptions

Owner Liability: In designated open range, livestock owners are generally not liable; in herd districts, owners must confine animals or face negligence claims.

Plain-Language Summary: Idaho’s “open range” tradition gives owners broad protection, but liability can attach in herd districts or when animals are deliberately driven onto roads.

Context & Details:

Much of Idaho is still considered open range, meaning drivers have a duty to avoid livestock, not the other way around. However, counties can establish herd districts requiring containment; in those areas, livestock on the road may trigger owner liability if negligence is shown. Key evidence includes local maps or ordinances showing herd district boundaries, witness statements about habitual escapes, and fencing conditions in restricted zones. Plaintiffs outside herd districts face an uphill battle unless they can prove intentional or reckless conduct, such as knowingly leaving gates open near a busy highway.

Sources: Idaho Code § 25-2118 (Open Range) · Idaho Code § 25-2402 (Herd Districts)

Indiana Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from straying; failure to do so can result in negligence liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Indiana law expects livestock owners to exercise reasonable care in keeping animals off roadways, and liability often hinges on barrier maintenance.

Context & Details:

Under Indiana law, livestock owners cannot allow animals to roam at large, and they face liability when escapes occur due to inadequate fencing, poor supervision, or ignored warnings. Rural areas with aging agricultural infrastructure are common problem spots. Evidence such as weather records (to counter “storm damage” defenses), neighbor testimony, and prior complaints to local authorities can be decisive. Indiana’s framework is firmly fenced-in, making it a generally plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction.

Sources: Ind. Code § 15-17-18-8

Iowa Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must restrain livestock; liability arises from inadequate containment or other negligent acts.

Plain-Language Summary: Iowa law requires livestock to be kept off public roads, supporting claims when owners fail to maintain adequate barriers.

Context & Details:

Iowa imposes a statutory duty to prevent livestock from running at large, and owners can be held liable when their failure leads to accidents. Courts often examine the history of escapes, the condition of fences, and the reasonableness of inspection routines. A strong claim typically includes photographic evidence of the enclosure, witness accounts of habitual escapes, and proof of prior official warnings. Owners may argue unforeseeable events like vandalism, but such defenses rarely succeed without documentation.

Sources: Iowa Code § 169C (estray)

Kansas Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Open Range with Local Exceptions

Owner Liability: Liability depends on whether the incident occurred in open range or within a local stock-restricted district.

Plain-Language Summary: Kansas law largely follows an open range model, but stock-restricted districts require containment and allow for negligence-based claims.

Context & Details:

In open range areas, livestock owners have no general duty to prevent animals from being on the road, shifting the responsibility to drivers. However, in counties or districts that have adopted stock laws, owners must confine animals and may be liable for damages caused by escapes. The first step in any claim is verifying whether the accident site falls within such a district. Evidence like local ordinances, prior citations, and fencing conditions can be critical. Plaintiffs in open range zones face a steep burden unless they can prove intentional misconduct or violation of a specific law.

Sources: K.S.A. 47-122

Louisiana Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Fenced-In with Rural Exceptions)

Owner Liability: Liability depends on location; rural parishes may follow looser rules unless local ordinances require containment.

Plain-Language Summary: Louisiana blends fenced-in principles with rural exceptions, so a claimant’s prospects depend heavily on where the incident occurred.

Context & Details:

In many Louisiana parishes, especially rural ones, livestock can roam unless local ordinances require fencing. In such “open range” areas, plaintiffs must show more than mere presence of livestock — they must prove the owner knowingly allowed animals on the roadway or failed to act after prior incidents. In parishes with fencing requirements, negligence is easier to establish through evidence of poor maintenance or ignored complaints. Checking parish-level laws and gathering photographic proof of inadequate enclosures are essential first steps.

Sources: La. R.S. 3:2803 (Highways) · La. R.S. 3:3003

Maryland Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In / Negligence

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; liability arises from failure to exercise reasonable care.

Plain-Language Summary: Maryland’s livestock laws require containment, with owners liable for damages caused by escapes due to negligence.

Context & Details:

Maryland imposes a statutory duty to keep livestock from roaming, and courts typically require proof that the owner failed to maintain barriers, secure gates, or respond to escape warnings. Rural areas near highways see the most incidents, often involving aging fencing and inattentive supervision. Claimants can strengthen their case with photos, neighbor accounts, and prior incident reports. Maryland’s approach makes it generally favorable to plaintiffs.

Missouri Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Fenced-In with Open Range Areas)

Owner Liability: Liability depends on whether the county follows the general law (fenced-in) or retains open range rules.

Plain-Language Summary: Missouri’s approach varies widely by county; plaintiffs in fenced-in counties have stronger claims than those in open range zones.

Context & Details:

Under Missouri law, most counties have adopted a fenced-in requirement, making owners liable when livestock escape due to negligence. However, some counties remain open range, where drivers bear the burden of avoiding animals. Verifying the county’s status is essential before proceeding. In fenced-in areas, strong evidence includes photographs of inadequate fencing, witness accounts, and prior citations for escapes.

Sources: Mo. Rev. Stat. § 270.010

Nebraska Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Nebraska imposes a general duty to keep animals contained, with clear statutory backing.

Context & Details:

Nebraska law makes livestock owners responsible for preventing animals from escaping and running at large. Courts often evaluate whether the owner took reasonable steps to maintain fences and respond to known hazards. Frequent defenses — like blaming third parties or extreme weather — are scrutinized closely, and owners usually need strong proof to avoid liability.

Sources: Neb. Rev. Stat. § 17-547 (municipal) · Neb. Rev. Stat. § 54-304

New York Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from straying; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: New York follows a containment rule but often weighs the specifics of rural vs. suburban conditions.

Context & Details:

Courts consider both statutory duty and common-law negligence. In farming regions, claims often involve disputes over whether an escape was foreseeable or preventable. Weather events, vandalism, or sudden animal behavior are common defenses, but prior incidents weaken those arguments considerably.

Sources: Hastings v. Sauve, 21 N.Y.3d 122 (2013)

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in New York?

Ohio Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Fenced-In

Owner Liability: Owners must prevent livestock from running at large; negligence or statutory violation supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Ohio’s standard is straightforward: contain livestock or face potential liability.

Context & Details:

Ohio law prohibits livestock from running at large, and violations can trigger civil and criminal consequences. Claims often involve neglected fencing, improperly latched gates, or repeat incidents. Defenses based on third-party interference require solid proof.

Sources: Ohio Rev. Code § 951.02

Oklahoma Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range in some counties; Fenced-In elsewhere)

Owner Liability: Open range limits liability; fenced-in counties impose negligence-based liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Oklahoma’s rules shift with county law — plaintiffs must confirm the jurisdiction’s doctrine first.

Context & Details:

County commissioners can designate areas as stock districts requiring containment. Rural ranching areas often remain open range, protecting owners from most claims absent willful misconduct. County-level research is often the starting point in any Oklahoma livestock accident case.

Sources: 4 O.S. § 98

South Dakota Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range in some areas; Fenced-In elsewhere)

Owner Liability: Liability depends on jurisdiction; open range shields owners, fenced-in areas hold them accountable for negligence.

Plain-Language Summary: South Dakota’s livestock laws hinge on whether the accident occurred in open or closed range territory.

Context & Details:

Many western counties retain open range traditions, while eastern areas are often fenced-in. County commission designations and local ordinances determine the applicable rule.

Sources: S.D. Codified Laws § 43-23-1 et seq.

Texas Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Predominantly Open Range (with closed range by local option)

Owner Liability: Open range limits liability; closed range imposes containment and negligence standards.

Plain-Language Summary: Texas defaults to open range but allows counties to adopt stock laws creating closed range areas.

Context & Details:

Ranching heritage keeps open range alive in many rural counties, but numerous counties have passed local stock laws requiring fencing. Plaintiffs must first determine whether the accident site is in a closed range area.

Sources: Tex. Agric. Code § 143.024 (state highways) · Tex. Agric. Code § 143.102 (county stock laws)

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Texas?

Utah Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range unless designated otherwise)

Owner Liability: In open range, owners generally aren’t liable without willful misconduct; closed range imposes negligence liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Utah’s standard depends on whether the accident occurred in open or closed range territory.

Context & Details:

County and municipal designations are key. Plaintiffs often need to obtain maps or records to confirm the area’s status before building a negligence case.

Sources: Utah Code § 4-26-104

Dig deeper: Who Pays If You Hit a Cow or Other Livestock in Utah?

Washington Mixed / County-Dependent

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range unless closed by county ordinance)

Owner Liability: Open range protects owners; closed range requires containment and allows negligence claims.

Plain-Language Summary: Washington defaults to open range, but counties can declare closed range zones.

Context & Details:

Local designations determine liability. Plaintiffs should document jurisdictional status early.

Sources: RCW 16.24.065

Defendant-Friendly States – Livestock Accident Liability

Montana Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Predominantly Open Range (with herd districts that operate as fenced-in zones)

Owner Liability: In open range areas, owners are generally not liable unless willful misconduct is shown; in herd districts, negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Montana defaults to open range, but liability shifts in designated herd districts where fencing is required.

Context & Details:

Most of Montana is open range, meaning livestock may legally roam and vehicle operators have the duty to avoid collisions. Plaintiffs in open range areas face an uphill battle unless they can prove intentional release or egregious neglect (e.g., turning animals loose onto a busy highway). In herd districts, owners must keep livestock fenced in; broken fences, ignored escape reports, or repeated incidents often tip cases in favor of plaintiffs. County boundary maps and herd district designations are critical to determining which standard applies.

Sources: Mont. Code Ann. § 60-7-201

Nevada Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range outside “fenced” or “herd” districts)

Owner Liability: In open range, owners are not liable absent willful misconduct; in herd districts, negligence supports liability.

Plain-Language Summary: Nevada’s rules depend on whether the land is designated open range or fenced-in by law.

Context & Details:

Open range is common in Nevada’s rural counties, meaning livestock can legally roam and motorists must be alert. However, counties may establish herd districts where livestock must be fenced in. Liability shifts dramatically in these areas, with owners facing potential civil responsibility for poor containment. Determining jurisdiction — and whether signage or fencing was legally required — is often a decisive first step in any claim.

Sources: NRS 568.360

New Mexico Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Predominantly Open Range (with exceptions for incorporated areas and designated districts)

Owner Liability: In open range, owners generally aren’t liable unless willful misconduct is shown; fenced-in areas impose negligence liability.

Plain-Language Summary: New Mexico’s standard depends on location — open range law dominates rural areas, but cities and herd districts require containment.

Context & Details:

The state’s open range tradition is strong, meaning free-roaming livestock is lawful in most rural settings. Still, incorporated municipalities and specially designated herd districts mandate fencing, shifting responsibility to the owner. Plaintiffs must first establish that the accident occurred in a fenced-in jurisdiction before focusing on proof of neglect.

Sources: N.M. Stat. § 77-14-1 · N.M. Stat. § 77-16-1

North Dakota Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range in some areas; Fenced-In elsewhere)

Owner Liability: Liability depends on location; open range areas protect owners, fenced-in areas favor plaintiffs.

Plain-Language Summary: North Dakota’s system is location-driven — open range limits owner liability, fenced-in zones impose it.

Context & Details:

Ranching-heavy counties often maintain open range, but herd districts require owners to keep livestock enclosed. Determining the accident site’s legal designation is essential. Plaintiffs in open range areas face steep challenges unless willful misconduct can be shown.

Oregon Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Mixed (Open Range unless closed by county ordinance)

Owner Liability: In open range, owners generally aren’t liable without willful misconduct; closed range imposes containment duties.

Plain-Language Summary: Oregon defaults to open range but allows counties to declare closed range zones.

Context & Details:

Most litigation focuses on whether the area was officially closed range at the time of the incident. In closed range, owners must maintain adequate barriers, and failure to do so can create liability. Plaintiffs should gather county code references and signage records.

Sources: ORS 607.045 · ORS 607.005 (definitions)

Wyoming Defendant-Friendly

Doctrine: Predominantly Open Range (with herd districts requiring fencing)

Owner Liability: Open range limits liability; herd districts impose containment duties.

Plain-Language Summary: Wyoming’s standard depends on whether the incident occurred in open range or a herd district.

Context & Details:

Most of Wyoming is open range, giving livestock owners broad protection unless willful misconduct is shown. In herd districts, fencing is mandatory and negligence can result in liability.

Livestock Accident FAQ

I hit a cow on the road – who’s responsible?

Responsibility depends on where the accident happened and the laws in that state. In many states, livestock owners have a legal duty to keep their animals fenced in and off the road. If the owner failed to maintain proper fencing or allowed the cow to roam freely, they may be liable for the damages. However, in some “open range” states, livestock are allowed to roam, and drivers are generally responsible for avoiding them. Determining fault usually requires investigating local laws, the location of the accident, and whether negligence was involved.

What happens if you hit a cow with your car?

Hitting a cow can cause serious damage to your vehicle and potentially severe injuries to you or your passengers. The accident will typically be treated like any other collision, meaning you should report it to law enforcement, seek medical attention if needed, and contact your insurance company. In many cases, the cow’s owner or their insurer may also become involved if there’s evidence they were at fault for the animal being on the road.

What should I do after hitting a cow or horse?

Your actions right after a livestock crash can influence how the claim moves forward. Here’s what to prioritize:

- Call the police and report the crash. A formal report helps establish the key facts of the situation.

- Take photos. Snap pictures of the animal, vehicle damage, and the surrounding area, including fencing, gates, road conditions, skid marks, and any signage nearby.

- Look for identification. Tags, brands, or nearby property signs could indicate ownership. However, it’s safest not to get too close to the animal, which could be dangerous even if injured.

- Get medical attention. Even if injuries seem minor, see a doctor immediately. Some serious conditions only surface later.

- Speak with an attorney who handles livestock collisions. Early action helps preserve evidence and clarify responsibility.

Collisions like this often raise questions about fencing, livestock control, and who was responsible. When an animal ends up on a public road, the facts matter. Gathering information early can help show how the animal got loose and whether the owner failed to prevent the crash.

Who pays if you hit a cow on the road?

Who pays depends on state law.

- In fenced-in states, livestock owners are usually liable if their animals were loose due to poor fencing or negligence.

- In open range states, drivers often bear the risk and may have to cover their own damages unless the owner acted recklessly or the crash happened on a fenced or restricted highway.

An attorney familiar with livestock accident cases, like Silva Injury Law, can help determine who should pay.

Can you sue if you hit a cow?

Yes — if there is evidence that the livestock owner’s negligence caused the accident. A lawsuit may be appropriate if the owner failed to maintain fences, ignored previous incidents of livestock escaping, or otherwise violated applicable laws. In some states, strict liability rules apply, meaning the owner can be held responsible regardless of negligence. In open range states, however, suing may be much more difficult unless you can prove reckless behavior by the owner.

What’s the average settlement for hitting a cow?

There’s no fixed “average” settlement because outcomes vary widely depending on:

- The severity of your injuries

- The extent of vehicle damage

- Applicable state laws

- Whether fault can be clearly established

Settlements can range from a few thousand dollars for property damage only to hundreds of thousands if serious injuries are involved. A lawyer experienced in livestock-related crashes can help you understand the potential value of your case.

Contact Silva Injury Law for Help with Livestock Collision Claims

If a loose cow or horse caused your injuries, you may have a claim against the owner. These cases often turn on the location of the crash, the condition of nearby fencing, and what the law requires from livestock owners.

Silva Injury Law has years of experience representing drivers injured in collisions with animals on the road. Our seasoned advocates are prepared to work to review the facts, examine who was responsible for keeping the animal contained, and pursue claims when the law supports them.

Contact us anytime to speak with a member of our team about a free consultation.